HVAC Training Pathways: Hands-On Courses and Career Outcomes

Outline

– Choosing Your HVAC Training Path: Certificate, Degree, or Apprenticeship

– What Hands-On HVAC Courses Actually Teach

– Licensing, Certifications, and Safety Requirements

– Career Outcomes and Earnings: From Helper to Specialist

– Planning Your First 24 Months: A Practical Roadmap

Introduction

Heating, ventilation, air conditioning, and refrigeration keep homes comfortable, protect food supply chains, and anchor energy efficiency goals in every region. That reach explains why the field attracts people who like solving practical problems with tools, meters, and a steady plan. The challenge is deciding how to train: a short certificate, a two‑year degree, or an apprenticeship that pays while you learn. This article brings those options into focus, explains what you actually do in a hands‑on course, and connects training choices to real job titles, safety requirements, and earnings expectations.

Choosing Your HVAC Training Path: Certificate, Degree, or Apprenticeship

Every HVAC journey starts with a tradeoff: time, money, and how quickly you want to be employable. Certificate programs are designed for speed. Typical tracks run 6–12 months and focus on core skills such as electrical basics, refrigeration cycle, brazing, system charging, recovery, and airflow diagnostics. The goal is employability for entry‑level installer or maintenance roles. You graduate with targeted skills, light general education, and often the exam prep needed for a refrigerant handling credential. If you prefer a quick start and are comfortable adding depth on the job, this pathway is appealing.

Associate degree programs usually take 18–24 months and layer general education courses with technical labs. The extended timeline lets you practice math used in load calculations, dig into controls and basic programming, and explore building science topics like ventilation strategies and envelope impacts. You also get time to complete multiple internships or co‑ops. Graduates often step into service technician roles faster or into environments where documentation, customer communication, and light project coordination are expected. If you want broader theory, a stronger resume signal, and more time in the lab before full‑time work, this route has advantages.

Apprenticeships combine paid work with classroom instruction over 3–5 years. You collect hours under a licensed mechanic, attend evening or block classes, and build a log of competencies signed off by supervisors. The big advantage is earning while learning and graduating with thousands of hours of verifiable experience. The tradeoff is pace: advancement is deliberate, schedules can be demanding, and coursework is spread out across seasons. For many, the stability and structured mentorship outweigh the longer journey.

To compare at a glance:

– Certificates: 6–12 months; lower upfront cost; faster entry; focused skills.

– Associate degrees: 18–24 months; broader academics; stronger theory; often more internship options.

– Apprenticeships: 3–5 years; paid from day one; structured progression; robust experience log.

Which path fits you? If you want the quickest on‑ramp, certificates are compelling. If you prefer a deeper foundation and more flexibility across roles, the associate route is one of the top options. If you value steady income, mentorship, and a clear competency ladder, apprenticeships are well‑regarded. All three can lead to similar mid‑career outcomes; the differences show up in timing, confidence with theory, and the network you build along the way.

What Hands-On HVAC Courses Actually Teach

Ask any seasoned technician what made training stick and they’ll mention labs—the place where copper hisses, gauges twitch, and airflow finally “clicks.” A solid hands‑on course teaches the essentials with repetition and realistic faults, not just textbook diagrams. You learn electrical safety and measurement first: using a multimeter correctly, tracing low‑voltage versus line‑voltage circuits, identifying shorts, opens, and high‑resistance connections. You practice reading schematics, labeling wires, and documenting what you found in plain language so the next person can pick up where you left off.

The refrigeration cycle gets equal attention. You’ll assemble and braze copper joints, pull deep vacuum with a micron gauge, weigh in charge, and interpret superheat and subcooling. Instead of memorizing numbers, you compare readings across ambient conditions until patterns emerge. Recovery machines, recovery cylinders, and leak detection methods become second nature. In well‑run labs, instructors seed systems with common issues—undercharge, restricted filter‑driers, weak capacitors—so you experience the troubleshooting path: verify the complaint, observe pressures and temperatures, isolate, confirm, and correct.

Airflow and duct diagnostics tie comfort to the physics you can measure. You’ll use a manometer to read static pressure, check temperature rise across heat exchangers or coils, and relate blower speeds to target airflow. Simple adjustments—sealing returns, balancing registers, or fixing a kinked flex run—often earn their keep quickly. Combustion safety and venting are covered for fuel‑burning equipment: draft checks, verifying combustion air, testing for spillage, and recognizing cracked heat exchangers or venting errors that require immediate shutdown and reporting.

Controls and emerging technologies appear throughout. Courses may introduce basic building automation concepts, sensors and actuators, economizer logic, and variable‑speed equipment behavior. On the refrigeration side, you might see reach‑in cases, walk‑in boxes, defrost strategies, and proper piping practices to protect compressors. Tools become your second language:

– Electrical: multimeter, clamp meter, non‑contact tester, lead set for continuity.

– Refrigeration: gauges or digital manifold, micron gauge, scale, vacuum pump, leak detector.

– Air and combustion: manometer, anemometer, psychrometric charting, combustion analyzer.

Finally, soft skills are woven in because they keep jobs on track. You’ll write service notes that stand up to scrutiny, practice professional customer communication, and learn to stage parts orders. Safety routines are drilled until automatic: lockout/tagout, fall protection basics, brazing PPE, cylinder handling, ladder use, and housekeeping. By the end, a good course leaves you with a small portfolio—photos of your brazed joints, sample diagnostics, and checklists—that shows what you can actually do.

Licensing, Certifications, and Safety Requirements

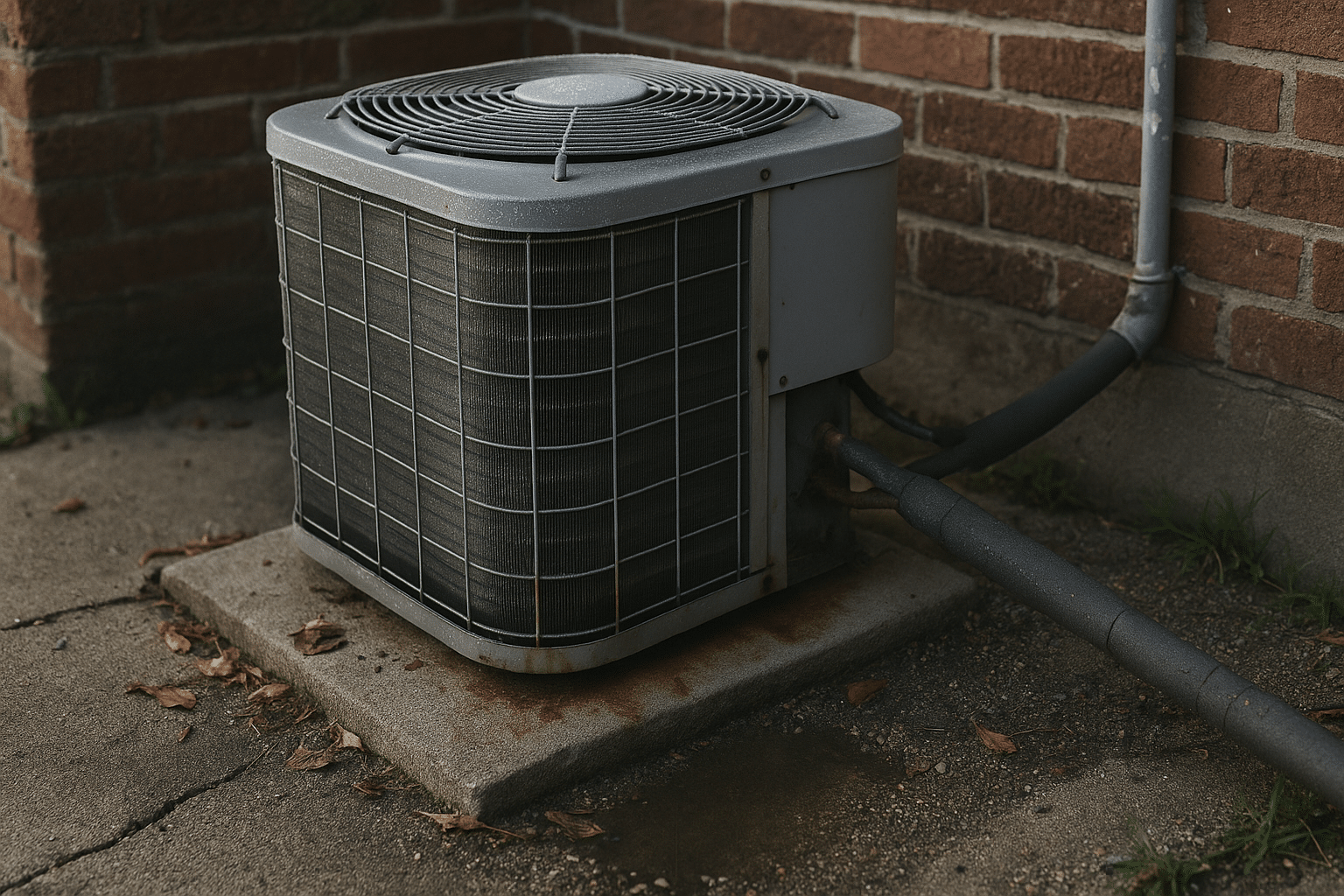

HVAC work touches electricity, combustion, pressurized refrigerants, and roofs or ladders. That mix demands credentials and habits that protect people and property. Requirements vary by country, state, and municipality, but most regions share a core structure. First, anyone handling regulated refrigerants typically needs a federal or national credential demonstrating knowledge of safe recovery, charging, and environmental rules. In the United States, this is commonly referred to as a Section 608 credential, and many employers require it before you can connect gauges to a system.

Second, local licensing may apply to the trade or to scopes of work. Some jurisdictions license technicians or contractors for mechanical work, others tie licensing to specific systems like hydronics, sheet metal, or gas piping. Classroom programs often embed exam preparation into the curriculum, covering code navigation, calculations, and practical scenarios. Apprenticeships align classroom hours with licensing milestones so that by the time you test, your logbook reflects real tasks performed under supervision.

Safety training is non‑negotiable. Expect coursework or cards covering:

– Electrical safety, arc flash awareness, and proper PPE selection.

– Lockout/tagout procedures to control hazardous energy.

– Fall protection and ladder safety for rooftop and attic work.

– Hot work permits for brazing and soldering.

– Confined space awareness in mechanical rooms and crawl spaces.

– Cylinder storage, transport, and recovery best practices.

Beyond credentials, policies are tightening around leak reduction, recordkeeping, and refrigerant transition management. Technicians increasingly document recovered quantities, track equipment with serialized tags, and follow changing rules around phasedown schedules. Staying current means continuing education—short refreshers on new refrigerants, updated charging methods, or revised ventilation requirements. Employers value pros who bring both a safety mindset and the paperwork discipline that keeps audits uneventful.

Practical tip: assemble a “compliance kit” in your truck or backpack. Include copies of your credentials, a simple job hazard analysis form, a lockout/tagout tag set, calibration records for critical meters, and a small binder with standard operating procedures. This small habit signals professionalism, speeds site check‑ins, and reduces costly return trips. Training programs that simulate this admin flow in class give graduates a head start the first week on the job.

Career Outcomes and Earnings: From Helper to Specialist

HVAC careers span more than swapping filters and tightening belts. Early roles include installer helper, maintenance technician, or shop fabricator. These positions build tool familiarity, safe work habits, and customer etiquette. Within a year, motivated techs often move into service calls with guidance, handling common issues like failed capacitors, dirty coils, and airflow imbalances. As confidence grows, so does responsibility: commissioning new systems, documenting warranty claims, and training newer helpers.

Specialization expands options and earnings. Many professionals gravitate toward one of several tracks:

– Residential/light commercial service: steady mix of maintenance and repairs; strong customer interaction.

– Commercial HVAC: larger rooftops, split systems, and simple controls; more documentation and scheduling.

– Refrigeration: walk‑ins, reach‑ins, ice machines; emergency calls and food safety stakes.

– Hydronics and boilers: piping, pumps, and combustion; seasonal tune‑ups and retrofits.

– Controls and building automation: sensors, sequences, and trending; a blend of electrical and IT.

Compensation varies with region, sector, overtime, and certifications. National surveys routinely show steady, middle‑income wages for technicians, with premiums for on‑call rotation, night work, or industrial sites. Experienced specialists who handle complex refrigeration, large boilers, or advanced controls often command higher hourly rates. Project leads, estimators, and service managers earn more as they balance field knowledge with planning, sales support, and team coordination. Some choose self‑employment after building a client base and mastering scheduling, inventory, and billing—an entrepreneurial path that rewards organization as much as wrench skill.

Job stability is a notable draw. Heating and cooling are essential services, and federal labor data consistently shows demand that tracks population growth, construction activity, and equipment replacement cycles. Energy efficiency incentives and the shift toward heat pumps and smart controls are creating new service niches. For those who like measurable progress, the field offers clear markers: logged hours, passed exams, completed startups, and customer reviews. You can see your growth in fewer callbacks, faster diagnostics, and cleaner documentation.

The takeaway: entry‑level roles reliably lead to higher‑skill assignments when you combine hands‑on practice, continuing education, and safety discipline. Choose a sector that fits your temperament—steady maintenance routes or puzzle‑heavy diagnostics—and let your logbook tell the story of your advancement.

Planning Your First 24 Months: A Practical Roadmap

New technicians succeed when they pair curiosity with structure. Consider this two‑year roadmap you can adapt to any training pathway. Months 0–3: focus on fundamentals. Build a daily checklist—PPE ready, charged batteries, calibrated meters, clean hoses. Shadow experienced techs and keep a small notebook of faults, readings, and fixes. Learn to stage parts and keep van or tool bag organization consistent. Practice documentation until it’s clear, concise, and repeatable. Obtain required refrigerant handling credentials and basic safety cards as early as possible.

Months 4–9: deepen diagnostics. Ask for practice on brazing and pressure testing during slower hours. Volunteer to lead simple maintenance visits while a senior tech observes. Create a personal “baseline library” by recording normal superheat, subcooling, and static pressure across common system sizes and outdoor conditions. These references make outliers stand out on future calls. Start building a small portfolio—photos of clean brazed joints, screenshots of vacuum levels, and sample service notes—with sensitive details removed.

Months 10–15: expand scope. Take on commissioning checklists for new installs, including airflow verification and controls setup under supervision. Learn to quote small repairs by referencing price books and time estimates. If your area uses specific energy efficiency tests, request exposure to those procedures. Add complementary skills like basic sheet metal adjustments, drain slope fixes, or simple control wiring for accessories. Begin tracking your job hours by category (installation, service, maintenance, refrigeration, controls) so you can present a clear picture during reviews.

Months 16–24: specialize thoughtfully. If refrigeration calls energize you, request more walk‑in or reach‑in assignments and pursue advanced coursework. If building automation intrigues you, ask to shadow commissioning agents and learn trend logging. For residential comfort, focus on airflow correction and indoor air quality accessories. At this stage, your goals should include:

– Reducing callbacks through disciplined testing and documentation.

– Passing any local licensing exams tied to your scope of work.

– Demonstrating safe, efficient solo work on routine tasks.

– Communicating clearly with customers and office staff.

Throughout the two years, keep three habits: review manuals for systems you service, reflect after each job on what you’d do differently, and schedule periodic calibration checks for instruments. Simple discipline compounds, and it shows up as trust from dispatchers, fewer return trips, and opportunities to tackle more complex assignments.

Conclusion

Whether you choose a fast certificate, a deeper two‑year degree, or a steady apprenticeship, HVAC offers a realistic path to stable, hands‑on work with room to grow. Start with a training format that fits your timeline and finances, practice lab skills until they’re automatic, and collect the safety and refrigerant credentials your region requires. Then let momentum build: document your wins, seek varied assignments, and choose a specialization that keeps you curious. With that approach, your tool bag comes with a plan—and your plan leads to meaningful, measurable progress.